INTRODUCTION

The fields of Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology are considered by researchers and practitioners as complimentary and ‘natural partners’ due to their mutual focus on well-being, growth, and peak human potential and functioning (Biswas-Diener, 2010; Burke, 2018; Kauffman & Linley, 2007). Positive Psychology (PP) is the scientific study and practice of optimal human functioning and flourishing (Linley et al., 2006). By comparison, Coaching Psychology (CP) is the application of psychological approaches, processes and interventions to coaching practice grounded in established psychological theories (Passmore et al., 2018).

Given the natural connection between PP and CP, numerous calls have been made for their integration (Biswas-Diener, 2010; Grant & Spence, 2010; Green & Palmer, 2019; Kauffman, 2006). Such an integration forms the basis of the emerging field of Positive Psychology Coaching (PPC), described as the application of positive psychology using evidence-based approaches within coaching (Passmore & Oades, 2014). Applying PPC helps clients enhance their strengths, well-being, and performance and reach their goals (Boniwell & Kauffman, 2018).

According to Burke (2018), there is a surge of empirical literature regarding the application of PPC within a coaching practice. Yet, there was a lack of a coherent application and a systematic approach to the scope of a PPC practice. As such, Burke (2018) proposed a Conceptual Framework for a Positive Psychology Coaching Practice with practitioners in mind to guide the practice of PPC while ensuring a well-informed and ethical application of PP in coaching.

Furthermore, Burke (2018) asserts that the Conceptual Framework was the first to map out the scope of a PPC practice that integrates PP and CP in a coaching practice. The Conceptual Framework was developed to assist coaching practitioners with a systematic approach to practicing PPC in their coaching. It provides educators with the knowledge and skills needed by coaches and ensures a well-informed and ethical application of PP in coaching. The Conceptual Framework also adopts an integrated approach based on the strong foundations of PP research and theory, the application of strength-based coaching models, and evidence-based practices that can advance the optimal functioning of clients.

Six elements comprise the Conceptual Framework (Burke, 2018): 1. having an in-depth knowledge of both PP and CP as a prerequisite for a coaching practice; 2. focusing on human strengths and the use of strengths-based models (Grant, 2011) and/or Solution-Focused Brief Coaching (Iveson et al., 2012) or Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987) to help clients reach their goals; 3. utilizing positive diagnosis for peak performance (Biswas-Diener, 2010); 4. co-creating client’s optimal-functioning goals; 5. utilizing Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs) to help enhance positive affect (e.g., Bryant & Veroff, 2007), or assist clients toward a specific purpose, e.g., creating best possible self (King, 2001); and 6. utilizing positive scales to measure the positive traits of clients. According to Burke (2018), all six elements must ideally be present and work together in tandem. The absence of an element may mean that PP is not fully integrated within a coaching practice.

The introduction of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework is timely since coaches are increasingly interested in incorporating positive psychology into their coaching practice. However, a review of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework in practice is limited. This international research study investigates Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework and its practical ‘on the ground’ application with ICF-credentialed coaches who self-identify using PP in their coaching practice to understand better the coaches’ lived experiences in utilizing and applying positive psychology coaching in their coaching practice.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The research topic of Positive Psychology Coaching is underpinned by three areas: positive psychology, coaching psychology and coaching. Key aspects of these three fields are highlighted below to help better understand the landscape.

Positive Psychology

Positive Psychology (PP) is the scientific study and practice of optimal human functioning and flourishing (Linley et al., 2006). The Positive Psychology (PP) field was launched in 1998 by Martin Seligman to shift the perception away from the traditional psychology model, which solely focuses on dysfunction and disorder. The focus of PP is on the more positive aspects of human flourishing (Linley et al., 2003), such as well-being, happiness, personal strengths, flow, creativity, imagination, and wisdom of individuals and institutions, as well as flourishing at a group level (Hefferon & Boniwell, 2011). Positive Psychology is generally considered an ‘umbrella term’ overlapping with other disciplines and topics (Linley & Joseph, 2004). It has ties with humanistic psychology (Linley et al., 2003) and the influential works of Abraham Maslow on self-actualization (Maslow, 1968) and Carl Rogers on the fully functioning person (Rogers, 1961).

Positive Psychology is both a research science that investigates and studies optimal human functioning and an application of theory into practice (Green & Palmer, 2019). The application of PP is operationalized through Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs), which are intentional actions or methods of treatment to cultivate positive cognitions, feelings, or behaviours (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Examples of well-known PPIs include Gratitude (McCullough et al., 2002), Character Strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), and Three Good Things (Passmore & Oades, 2016).

Coaching Psychology

Coaching Psychology (CP) is the application of psychological approaches, processes and interventions to coaching practice grounded in established psychological theories (Passmore et al., 2018). The focus of CP is on individuals, organizations and groups that do not have significant mental health issues and/or abnormal levels of anxiety (Grant, 2008). The field of coaching psychology (CP) was launched by Anthony Grant in 2000 to address the frustration of coaches and practitioners regarding limited training and teachings available for well-functioning adults in applying psychological theories to their coaching practice (Grant, 2006). It has roots in humanistic psychological approaches to counselling, including but not limited to Cognitive Behavioural Coaching, Solution-Focused Coaching and Narrative Coaching (Palmer & Whybrow, 2008).

Similar to operationalizing PP through PPIs, CP is operationalized through ‘evidence-based coaching’ (EBC), described as the intentional use of current and best knowledge from valid theory and practice, and integrated with the practitioner’s expertise in deciding how to deliver coaching (Grant & Stober, 2006). This description recognizes that EBC is based on scientific theory and not ‘regular’ coaching, which may or may not be found in the science of CP (Green & Palmer, 2019). As such, the emergence of CP has assisted coaches in addressing what prominent coach Sir John Whitmore first observed:

“In too many cases, they [coaches] have not fully understood the performance-related psychological principles on which coaching is based. Without this understanding, they may go through the motions of coaching or use the behaviours associated with coaching, such as questioning, but fail to achieve the intended results” (Whitmore, 1992, p. 2).

Coaching

Coaching is widely described as a process of unlocking the potential of individuals to maximize their personal performance (Whitmore, 1992), although there has yet to be a consensus definition of coaching (Van Nieuwerburgh, 2017). Coaching for optimal performance and functioning was popularized in the 1980s through executive coaching (Green & Palmer, 2019). Before this, the application of coaching was limited to sports and performance (Passmore, 2015).

Professional coaching, i.e., coaching as a career and occupation and the practice of life, executive, team and other forms of coaching, has grown extensively since the 1990s (Gray, 2010). Coaching associations such as the International Association of Coaching (IAC), European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC), Association for Coaching (AC), and the International Coach Federation (ICF) have been established to maintain professional standards. However, the coaching industry remains unregulated (Grant, 2006), which presents issues for professional credibility since the absence of regulation means that any individual can call themselves a coach without censure (Passmore & Oades, 2016). Hence, incorporating PP and CP within coaching can add to the aim of strengthening the credibility of the profession.

Positive Psychology Coaching

Positive Psychology Coaching (PPC) is described as the application of positive psychology and evidence-based approaches within coaching (Passmore & Oades, 2014) for the enhancement of strengths, well-being, performance, and achievement of goals (Boniwell & Kauffman, 2018). The term ‘Positive Psychology Coaching’ (PPC) was first introduced by Robert Biswas-Deiener in 2007 in his book Positive Psychology Coaching (Biswas-Diener & Dean, 2007) to help practitioners integrate the principles of PP into coaching. Kauffman (2006) asserts that PP is the science at the heart of coaching. Biswas-Deiner (2010) argues that as a science, PP is well-equipped to elevate and inform the standard and tools of coaching practice.

An early exploration of a PPC approach suitable for use with coaching clients was reviewed by Passmore and Oades (2014), in which they highlighted four key positive psychological theories that underly PPC, including strengths theory (Proctor et al., 2011), broaden and build theory (Fredrickson, 2009), self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) and wellbeing theory (Seligman, 2011). These theories are included and build upon Burke’s Conceptual Framework (2018).

The beneficial effects of PPC include enhanced well-being and vitality (Govindji & Linley, 2007), higher work performance (Linley et al., 2009), and greater ability to carry on under challenging circumstances (Oades & Passmore, 2014).

In essence, Positive Psychology Coaching integrates Positive Psychology theory with the application of evidence-based coaching psychology approaches within the practice of coaching. The introduction of Burke’s Conceptual Framework (2018) is a starting point for discussions regarding a systematic approach to the scope of a PPC practice that integrates both positive psychology and coaching psychology. While there are models and frameworks that suggest how such an integration should be utilized within a coaching practice, there is no research that shows whether this actually occurs in practice, which is what this study sets out to do.

RESEARCH AIMS

The aim of this study is three-fold. First, it aims to understand better the ‘theory to practice’ aspect of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework on the lived experience of ICF-credentialed coaches who use positive psychology in their coaching practice.

Second, the study aims to inform future training and implementation for an integrated Positive Psychology Coaching practice.

Third, the study also aims to generate a new model to provide a conceptual visualization of the current situation faced by ICF-credentialed coaches who utilize positive psychology coaching in their coaching practice.

Key research questions for the study include:

-

What do the participants understand about positive psychology coaching?

-

To what extent are participants using all of the elements of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework?

-

What do participants value most about positive psychology coaching?

METHOD

Design

Due to the exploratory nature of the study, a qualitative methodology was chosen (Willig, 2013) using Constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz, 2014) for its theory-generating potential and for the emergence of a new conceptual framework about how coaches utilize and apply positive psychology coaching in their coaching practice. Through Constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz, 2014), there is flexibility in collecting data using semi-structured interviews. Constant comparative analysis allows for adapting the design in an iterative manner (Charmaz, 2014). Constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz, 2014) was selected for the Constructivist approach as through semi-structured interviews, the researcher can better understand how the participants construct their understanding of their lived experience based on an inductive ‘bottom-up’ process, whereby patterns in the data are observed, which can lead to a theory emerging from the data (Willig, 2013).

Participants

Initially, a purposive sample was used for this study (Charmaz, 2014). Since coaching is not a regulated industry, anyone can label themselves a coach regardless of their educational training, profession or experience (Grant, 2006, 2008). To protect against this threat to the integrity of the research, the major inclusion criteria required that participants who self-identified using positive psychology in their coaching be credentialed members of the International Coach Federation (ICF), a non-profit organization that sets standards and independent certification for professional coaching with over 56,400 members in 143 countries (ICF, 2023). The ICF has three paths for credential requirements (Associate Certified Coach, Professional Certified Coach, and Master Certified Coach). Participants from other accredited associations were not included to minimize excessive variability due to different levels of training, professional standards, and experience.

An electronic invitation letter was sent by ICF Headquarters (USA) to its members who expressed interest in participating in the research. The researcher contacted individuals who wished to participate. Those who met the inclusion criteria were invited to complete the Consent Form.

Demographics

Fourteen participants from eight countries (Australia, Canada, Finland, Greece, Mexico, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States) were included in the study. There were 13 females and one male ranging in age between 41-60 years old with 3-12 years of experience incorporating positive psychology into their coaching practice. Nine participants possessed a master’s degree, and three had a doctoral degree. Two participants had attained an Associate Certified Coach (ACC) accreditation level, while 11 had a Professional Certified Coach (PCC) level, and one at a Master Certified (MCC) level with the ICF.

Procedure

Following approval by the University of East London ethics board, recruitment began with all volunteers receiving a participant information sheet and consent form. The 14 participants then completed a pre-interview questionnaire that collected demographic information, including age, ICF level, years of coaching experience, education, and area of coaching specialty. A semi-structured questionnaire was used with pre-set and open-ended questions to encourage discussion and participant choice in what to share. Examples of questions included: “What is your knowledge and understanding of positive psychology?’ and 'What is your definition of positive psychology coaching?”. The interviews, lasted 60 – 75 minutes with a debriefing letter provided to participants at the end of each interview and time allowed for any participant questions about the research.

Data Analysis

Consistent with the Grounded Theory (GT) methodology, the interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded immediately after the completion of each interview for accuracy. It is important to note that GT is an iterative process with steps occurring simultaneously (Tie et al., 2020). However, the steps are outlined here as a linear process for explanatory purposes. There are four stages of GT coding. Stage One included initial line-by-line coding using “gerunds” (verbs ending with “ing”) to indicate action (Tie et al., 2019). Stage Two involved focused coding, which involved selecting the gerunds that were most relevant to the study research questions. Stage three involved axial coding and sorting the codes into categories, identifying emerging higher-frequency data and collapsing key categories as guided by the data (Corbin, 2017). Constant comparative analysis began after the second interview, looking for similarities and differences in the identified codes. Stage Four involved theoretical sampling and theoretical coding for the theoretical model to emerge (Charmaz, 2014).

The researcher also conducted memo writing and reflexivity following each interview and throughout the data analysis to capture thoughts and interpretations of the concepts’ relationships and connections (Charmaz, 2014). The process of making constant comparisons, asking questions, reflexivity and memo writing provided checks and balances to address the researcher’s potential biases and assumptions throughout the study (Charmaz, 2014).

FINDINGS

The data analysis resulted in the construction of three theoretical codes and nine axial codes (see Table 1), which have been grouped into the study’s three key research questions (see Research Aims) above.

The aim of the first key research question was to comprehend better the breadth and depth of the participants’ understanding, knowledge and awareness of positive psychology coaching. Hence, the following three interview questions were posed to the participants for this purpose:

-

What is your knowledge and understanding of positive psychology?

-

What is knowledge and understanding of coaching psychology?

-

Combining PP and CP, what is your definition of positive psychology coaching?

Based on the participants’ responses to these three interview questions, the data analysis generated the three categories and theoretical codes below. The participant names in the following statements have been changed to preserve their anonymity.

Axial Code 1.1: Wide-ranging knowledge levels of PP

The levels of knowledge of positive psychology were wide-ranging, from understanding PP as a field of science to PP as a source for positive thinking. One participant described PP as

'the science of seeing the outcomes repeatedly…not through shoddy research, but real research.’ (Linda)

However, another participant stated,

‘being honest, I only use it as a way of thinking’ (Beth)

while another participant noted,

‘it is a misunderstanding that people think it’s positive thinking. The smiley face.’ (Simone)

Axial Code 1.2: Wide-ranging knowledge levels CP

By comparison, there was less awareness and knowledge about the scientific field of Coaching Psychology (CP). Participants were much more familiar with PP than CP. Some participants were either discovering CP for the first time during the interview or believed that by default, CP referred to psychologists becoming coaches or practicing coaching. In some cases, the interview served as the first exposure to reflecting on CP and its role in coaching. This was acknowledged in numerous statements, including,

'There are lots of theories and models, so I don’t have a single definition of coaching psychology. Positive psychology is a little more refined in my mind.’ (Emma)

to the following statement by another participant,

'coaching psychology is the first time I hear about it. I know coaching. I know about psychology. Coaching Psychology, I don’t know’. (Judi)

Axial Code 1.3: Wide-ranging knowledge of PPC

There were also varying degrees of knowledge and comprehension regarding Positive Psychology Coaching as a field and term. The degree of comprehension ranged from having direct experience and training with PPC to discovering it for the first time as a professional title. The responses varied when defining PPC. One participant, for example, defined PPC as

“using the proven science of positive psychology as a technique in active coaching” (Olivia)

while another participant observed that,

"I don’t think I’ve ever heard anybody calling themselves a positive psychology coach." (Alice)

Theoretical Code 1 – Mixed Levels of Understanding

The data analysis and findings across the three axial codes of wide-ranging knowledge, variable awareness of CP and comprehension of PPC resulted in the construction of the first theoretical code of ‘mixed levels of understanding.’ The theoretical code captures the participants’ varying levels of understanding, awareness and knowledge of the current fields of positive psychology, coaching psychology and the emerging field of positive psychology coaching.

This also includes the participants’ recognition that PP and coaching are relatively young fields. One participant noted,

“these fields have only been around kind of 23ish years…there still are growing pains”. (Sophie)

Participants also recognized the need for a better connection between positive psychology and coaching psychology as they were more familiar with PP than CP. As one participant indicated,

“I think we do need to connect the dots between positive psychology and coaching psychology much more tightly than done at the minute.” (Emma)

This recognition was also extended to the participants, identifying the need for a consistent understanding of the terms and their meaning to avoid miscommunication based on semantics. For example, a participant suggested that,

“in order for positive psychology to really take hold…we need to adopt common terms and common language and common expectations.” (Amy)

Overall, the ‘mixed levels of understanding’ theoretical code addresses the first key research question regarding the participants’ understanding of positive psychology coaching and highlights the varied perspectives participants hold about the interconnected fields that constitute positive psychology coaching.

This research question aims to explore the extent to which the participants utilize all six elements of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework and identify gaps in practice. The six elements of the Conceptual Framework include: 1) having an in-depth knowledge of both PP and CP as a prerequisite for a coaching practice; 2) focusing on human strengths and the use of strengths-based models (Grant, 2011) and/or Solution-Focused Brief Coaching (Iveson et al., 2012) or Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987) to help clients reach their goals; 3) utilizing positive diagnosis for peak performance (Biswas-Diener, 2010); 4) co-creating client’s optimal-functioning goals; 5) utilizing Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs) to help enhance positive affect (e.g., Bryant & Veroff, 2007), or assist clients toward a specific purpose, e.g., creating best possible self (King, 2001); and 6) utilizing positive scales to measure the positive traits of clients. Burke (2018) asserts that all six elements must ideally be present and work together in tandem within a coaching practice for PP to be fully integrated.

During the interviews, the following five questions were posed to the participants, which resulted in the development of three additional categories and a second theoretical code noted below.

-

Which specific coaching model(s) or process do you use to help clients reach their goals?

-

How do you use positive diagnosis in your coaching to identify what is already working well for your clients to help them to maintain positive behaviours and/or peak performance?

-

Do you use Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs) to help clients increase and enhance their well-being? If so, which PPIs do you use?

-

Do you use positive psychology assessment measures and scales? If so, which ones do you use, or have used with clients?

Goals are integral to the coaching process. What is your approach to helping your clients to create and achieve goals for their optimal well-being and functioning?

Axial Code 2.1: Not Using All Six Areas

A majority of the participants did not utilize all six elements of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework. This includes not having an in-depth knowledge of both PP and CP, as noted above in the theoretical code of ‘mixed levels of understanding,’ as well as the utilization of Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs) and positive scales and measures. For example, some participants did not use any PPIs. This polarity is demonstrated by one participant who stated,

“All the tools I use is about strengths” (Alice)

while another noted,

“I don’t use positive psychology interventions. What I do is that I help people use their strengths as a toolbox to address some issues.” (Julie)

A strengths approach was widely used among participants as a PPI. Other PPIs utilized include PERMA (Seligman, 2011) and Gratitude (McCullough et al., 2002), which were more well-known to the participants.

The least utilized element by participants is PP assessment tools, with many wondering if they were using PP scales. For example, a participant stated,

"I use scales, but I don’t know if they are necessarily a positive psychology scale." (Sarah)

Category 2.2: Taking a pick-and-match approach

As noted in the ‘not using all six areas’ code above, most participants used a strengths approach as a form of PPI. A strengths approach was also used in multiple ways, including as an overall coaching approach, a means to help clients reach their goals, and an assessment tool through the Values in Action Survey (VIA: Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

In many instances, the participants had consciously decided not to use PPIs or PP scales in their coaching practice, as noted by the following responses,

“I choose not to use positive psychology interventions in my coaching.” (Mark), and

“I use strengths assessment. I don’t use PP scales, not sure what they are really.” (Judi)

In addition to preferences, it is also important to note that some participants did not use PPIs and/or PP scales in their coaching practice due to a lack of training and awareness of how to apply them. In other cases, participants had yet to receive training on administering and interpreting them.

Category 2.3: Taking identification from their niche

Given the varying degrees of awareness, understanding, and exposure to PP, CP, and PPC, a majority of participants did not identify with being a Positive Psychology Coach. Instead, they viewed themselves as a coach based on their specialty areas, such as a career coach, a transformational coach, a strengths coach, or a life coach. Other participants identified themselves as a professional credentialed coach based on their ICF accreditation. They also identified themselves as a coach based on their target audiences, such as a leadership coach who coaches leaders, a business coach who coaches entrepreneurs and professionals, or an executive coach who coaches executives and organizations.

The following two examples demonstrate the range of responses from,

“I don’t call myself a positive psychology coach. For me, they should be certified psychologists” (Judi) to

“Coaching is one of the things I do where I am applying positive psychology.” (Eva)

Theoretical Code 2: Missing Elements

The data analysis across the three axial codes of not using all six areas, taking a pick-and-match approach, and taking identification from their niche led to the construction of the second theoretical code of ‘missing elements’ in response to the second key research question regarding the extent to which participants utilize all elements of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework. The theoretical code also assisted in identifying gaps in practice, which one participant stated,

"what positive psychology brought was the research base that at the time coaching was missing." (Emma)

Since this research study aims to bridge the gap between the theory and practice of Positive Psychology Coaching to inform future training, the research question of what participants value most about Positive Psychology Coaching underscores the significance of understanding the importance of this coaching approach for the participants. Through the interviews, the following three questions were also posed to the participants:

-

To call themselves a positive psychology coach, what should they know or have the skills or background in?

-

What additional types of training or educational supports would you like to see being offered by ICF or other training or educational organizations to help you grow as a positive psychology coach?

-

Is there anything else that you would like to add that we did not cover?

Data analysis from these three questions revealed three distinct axial codes and the generation of the third theoretical code, described below.

Axial Code 3.1: Evidence-based practice

The participants valued the science of PP and particularly favoured grounding their coaching practice in evidence-based research. The participants also valued learning more about connecting coaching psychology to coaching outcomes and highlighting the return on investment of coaching. Furthermore, they viewed practicing PPC in an integrated way can help to increase their self-efficacy as a coach, as noted by a participant,

"positive psychology brought the research that I really felt I needed to stand tall in my coaching and feel like I was doing a good job with good reasons behind me." (Linda)

Participants also supported the need for flexibility. They valued a flexible approach in their coaching and using different tools beyond PP in service to their client’s needs. One participant stated,

"What I do with one person, I would not do with another". (Julie)

while another participant noted, noted,

"Each client is a different case study and I’m trying to pull just the right tools together to offer the support that individual client needs". (Tina)

Axial Code 3.2: Professional Training

In terms of the types of further training or educational support being offered, the participants favoured ongoing training through continuing education to build skills and grow as a coach. They also acknowledged that continuing education in PP is a necessary foundational training to support coaches who want to become a positive psychology coach.

At the same time, participants recognized the far-reaching variability in the coaching industry regarding the experience of coaches and the training and education offered by ICF-accredited and non-ICF-accredited organizations across the vast coaching landscape. This variability directly relates to what the participants raised as an issue for the coaching profession pertaining to the need for greater rigour and regulation overall in the coaching industry. This issue was perhaps the most concerning for the participants because the absence of legal protection for using the term ‘coach’ undermines the profession and their lengthy training and educational efforts to become certified credentialed coaches. Examples of concerns raised include,

“I’m big on credentials.,” (Judi) as well as the

"need to get this accreditation piece nailed down because anybody and their brother can hang out a shingle and say I’m a coach.’ (Amy)

Axial Code 3.3: Certification

Participants voiced their support of certification training in PPC as an effective means of ensuring that science-based strategies are being taught to coaches and used by coaches who are doing what one participant referred to as ‘certified work.’ This involves receiving the necessary foundational training in PP and ongoing training to become an agile coach and build on their skills. Since participants value the science of PP, they also favour grounding their coaching practice in evidence-based research. For example, a participant who is seeking more interventions noted,

"I would really like to see more empirical research about intervention and outcomes so that I could decide whether I’d like to incorporate in my practice." (Linda)

Moreover, in response to a question regarding types of training or educational supports needed to call oneself a positive psychology coach, a participant’s immediate response was

'well, certification in positive psychology coaching…more fundaments on the psychology… approaches or other tools, practices, case studies and research’. (Amy)

Theoretical Code 3: Integrated Approach

The data analysis across the three axial codes of evidence-based practice, professional training and certification led to the construction of the third and final theoretical code of ‘integrated approach.’ The theoretical code contributes to a better understanding of participants’ responses to the third key research question of what participants value most about positive psychology coaching. Moreover, the theoretical code contributes to considering the elements needed to enable the participants to confidently practice Positive Psychology Coaching in a more comprehensive and integrated way.

The ‘integrated approach’ theoretical code also helps to identify the supports and tools needed by the participants to inform future training, education and certification, thereby bridging the gap between the theory and practice of Positive Psychology Coaching.

Findings Summary

In summary, this research study revealed three main findings. The first main finding is that while integrating PP and CP within the application of coaching gains momentum in the academic community, ‘on the ground,’ the fields of PP and CP were understood and operationalized as separate and distinct fields. In fact, participants had varying awareness and understanding of the utilization and application of PP, CP, and PPC.

The second main finding is that participants did not utilize all six elements of Burke’s Conceptual Framework (2018), such as having an in-depth knowledge of both PP and CP, using positive diagnosis for peak performance, using Positive Psychology Interventions, and utilizing positive scales and measures. This was due, in part, to preferences, lack of awareness, or lack of training. Therefore, according to Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework, the participants in this research study had not fully integrated PP within their coaching practice and maximized its full potential. The consequences of this are that the coaches did not identify themselves as positive psychology coaches using instead their niche area to explain to clients their area of practice.

The third main finding is that participants value the science of PP and grounding their coaching practice in evidence-based research with greater integration into coaching psychology approaches and outcomes. They also valued further education, training and credentialing to fully practice and apply an integrated approach to Positive Psychology Coaching in their coaching.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this research study is three-fold. First, the study aims to understand better the ‘theory to practice’ aspect of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework on the lived experience of coaches who use positive psychology in their coaching practice.

Second, the study aims to inform future training and implementation for an integrated Positive Psychology Coaching practice.

Third, the study also aims to generate a new model to provide a visual conceptualization of the current situation faced by ICF-credentialed coaches who utilize positive psychology coaching in their coaching practice.

This section discusses the theoretical codes in relation to the relevant literature on PPC. This study can now shed light on how coaches are applying PPC into their coaching practice. This section also discusses constructing a new model to understand better the lived experience of coaches who use positive psychology in their coaching practice. Moreover, it offers a solution for future training and education for practicing a cohesive and integrated PPC. In addition, the study’s limitations and recommendations for new avenues of research are also discussed.

Theoretical Code 1: Mixed Levels of Understanding

The theoretical code of ‘mixed levels of understanding’ was constructed in response to the key research question 1: What do the participants understand about positive psychology coaching?

The theoretical code supports the findings related to the participants’ mixed levels of understanding and varying awareness and knowledge of the fields of PP, CP, and PPC (see Figure 1 below).

The mixed levels of understanding of PP, CP and PPC are also acknowledged in the literature (van Nieuwerburgh et al., 2018). Early attempts to integrate PP and CP fell within the purview of PPC (Biswas-Diener, 2010), whereby practitioners would employ various approaches, including but not limited to relying on a single PP element (Burke, 2018), choosing a PP scale, choosing from several PPIs (Susing et al., 2011), or applying a strengths-based approach to enable change (Linley et al., 2011). This approach is described by Van Nieuwerburgh et al. (2018) as a ‘pick and match’ strategy, with PPC having wide-ranging and varying interventions, some of which are vaguely connected to PPC.

The introduction of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework attempts to minimize the misinterpretation of PPC. However, utilizing all six elements of the Conceptual Framework can be challenging for coaches as it requires training in positive psychology, coaching psychology, strengths, PPIs and PP assessments and scales. As demonstrated in the data in this study, seasoned coaches with an average of seven years of experience incorporating positive psychology into their coaching practice did not have training in all six areas and, therefore, did not utilize the six elements of the Conceptual Framework. This challenge highlights the need for cohesive training and education to enable coaches to integrate positive psychology coaching into their coaching practice fully.

Theoretical Code 2: Missing Elements

The ‘missing elements’ theoretical code was constructed in response to key research question 2, "To what extent are participants using all of the elements of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework?". It serves as a conduit for understanding the participants’ approach to incorporating positive psychology into their coaching practice. It brings cohesion to understanding the gaps identified in the study, including taking a pick-and-match approach and not identifying as a Positive Psychology Coach.

As noted in the findings above, most participants take a strengths-based approach in their coaching, which, when applied to normal individuals, Green and Palmer (2019) assert that they can benefit the most from PPC. Lucey and Van Nieuwerburgh (2020) acknowledge that a strengths approach is integral to practicing PPC, which can lead to beneficial effects, such as enhanced vitality and well-being (Govindji & Linley, 2007), increased perseverance during challenges (Oades & Passmore, 2014), and greater work performance of leaders and direct reports (Linley et al., 2009).

While a strength approach is integral to practicing PPC, Burke (2018) argues that other elements must be included to practice PPC in an integrated and cohesive way. In fact, according to Burke (2018), if all six elements of the Conceptual Framework are not included and utilized, a coaching practice may not be maximizing and leveraging PP to its fullest potential. This was the case in this study. One of the consequences of coaches needing to utilize all six elements of the Conceptual Framework (Burke, 2018) and, therefore, not identifying as a Positive Psychology Coach is the lengthy training required to meet all six elements of the Conceptual Framework.

Theoretical Code 3: Integrated Approach

The theoretical code of ‘integrated approach’ was constructed in response to key question 3, 'What do participants value most about positive psychology coaching?'. As noted in the findings, while integrating PP and CP within the application of coaching gains momentum in the academic community, ‘on the ground,’ the fields of PP and CP were understood as separate and distinct fields, with participants having varying levels of knowledge and understanding of PP, CP and PPC. As such, the theoretical code of ‘integrated approach’ clarifies the support needed to benefit coaches, including training, education and certification to enable them to practice PPC in an integrated and cohesive way. It also helps to inform and guide researchers, educators and practitioners of future training of an integrated approach (see Figure 1).

There are ongoing discussions among scholars regarding the optimal integration of PPC. Van Nieuwerburgh et al. (2018) recognize that conceptualizing the integration of PP and coaching can be viewed conventionally and unconventionally. Conventionally, PP is viewed as a theoretical field, while coaching is viewed as an applied field. Unconventionally, the numerous psychological theories, applied practices, and evidence-based approaches do not necessarily derive from PP or CP but can be leveraged by both fields.

With regards to cohesively practicing PPC, Burke (2018) asserts that the Conceptual Framework is the first to map out the scope of a PPC practice in a comprehensive way with six key elements. However, the participants favoured a flexible rather than a prescriptive approach to practicing PPC. In fact, after decades of research in the field, Biswas-Diener (2020) reconsidered the topic of taking a prescriptive versus a flexible approach to practicing PPC and now supports a non-prescriptive approach, emphasizing that the focus needs to be on the quality of the coaching over PP in PPC. Hence, a solution for cohesive training in an integrated approach to positive psychology coaching is needed.

A New Model

Based on the study’s findings, key research questions, and the development of three theoretical codes (see Table 1), the construction of a new model is necessary. A new model helps better understand the lived experience of coaches who use positive psychology in their coaching practice. It also helps to address the gaps in practicing an integrated PPC to guide future training and education.

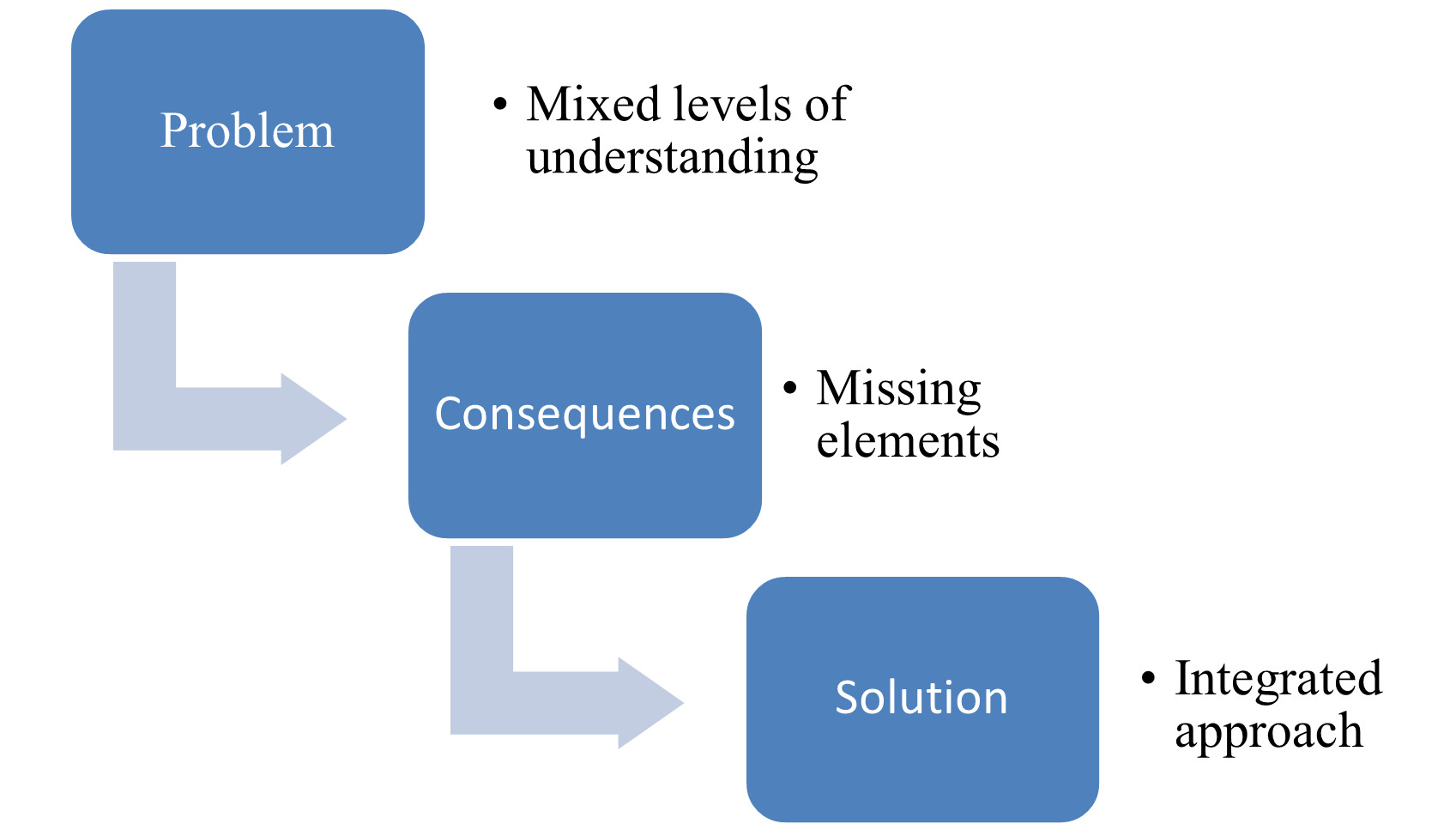

Figure 2, entitled Foundational Training Model for an Integrated Positive Psychology Coaching Practice, encompasses the findings and construction of the three theoretical codes, culminating in identifying the problem, consequences, and solution to helping coaches practice PPC in a focused, unified, and integrated way.

As highlighted in Figure 2, there is currently a mixed understanding, awareness and knowledge levels of the three fields of PP, CP and PPC. In practice, ‘on the ground,’ this mixed understanding also extends to coaches undertaking training and education in PP and/or CP with attempts to integrate them into PPC, which presents a gap in the training and education of coaches.

Moreover, Figure 2 highlights the consequences of having a mixed understanding, which has led to coaches not utilizing all of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework. Many chose a pick-and-match approach due to preferences, lack of awareness, or lack of training.

Given the problem of having mixed levels of understanding, which led to the consequences of the missing elements in Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework, Figure 2 highlights the solution needed for a focused and ‘integrated approach’ to help coaches practice PPC. The solution relates to taking a unified and targeted approach to offer evidence-based research, professional training and certification in PPC in a centralized manner so that coaches can focus on practicing and operationalizing PPC as one integrated field and approach.

Main Contributions of Study

The main contribution of this research study is providing clarity on the current state of practicing positive psychology coaching ‘on the ground’ with ICF-credentialed coaches who self-identify using positive psychology in their coaching practice. This is currently an under-researched area in the emerging field of positive psychology coaching. Another main contribution of this research study is the construction of a new model, entitled Foundational Training Model for an Integrated Positive Psychology Coaching Practice (see Figure 2), which underscores the importance of taking a three-pronged approach to combining evidence-based practice, professional training and certification as the solution to guide coaches to practicing PPC in a focused, integrated and cohesive way.

Limitations

While the study participants are credentialed coaches and members of the ICF and identical semi-structured interview protocols were followed, their skills and credentials varied at three separate levels: Associate, Professional, and Master Certified Coach. Their years of experience as coaches, training, educational background, and length of incorporating PP into their coaching were also varied. As such, their skills, credentials, and experience may have impacted the breadth and depth of their responses. This was also a small-scale study with only 14 participants.

Recommendations for Future Research

There is merit in furthering this area of inquiry in the following three ways. First, conduct the study with participants who have completed a positive psychology coaching training programme through either an academic institution or an accredited training organization. Second, replicate the study to include participants at the same coaching accreditation level rather than at any level or a mixed level. Third, conduct the study with the length of coaching experience of new coaches compared to seasoned coaches.

Implications for Practice

This international study is particularly relevant for coaching professionals, practitioners, educators, trainers, and researchers. The implications for practice underscores the importance of training that focuses on the intersection between Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology with evidence-based coaching so that coaches have access to cohesive training. This will help lower entry barriers for coaches, as they currently need to train in all three areas. Cohesive training will make positive psychology coaching more visible, and coaches will more readily be able to self-identify as positive psychology coaches rather than rely on identifying themselves based on their coaching niche.

CONCLUSION

This international research study investigated the use of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework and its practical ‘on the ground’ application with 14 ICF-credentialed coaches who self-identify using PP in their coaching practice. The aim of the study was three-fold. First, the study aimed to understand better the ‘theory to practice’ aspect of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework on the lived experience of coaches who use positive psychology in their coaching practice. Second, the study aimed to inform future training and implementation for an integrated Positive Psychology Coaching practice. Third, the study also aimed to generate a new model to provide a visual conceptualization of the current situation faced by ICF-credentialed coaches who utilize positive psychology coaching in their coaching practice.

The study was guided by the following three key research questions:

-

What do the participants understand about positive psychology coaching?

-

To what extent are participants using all of the elements of Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework? and

-

What do participants value most about positive psychology coaching?

The study utilized Constructivist Grounded Theory (Charmaz, 2014), which revealed three main findings. The first main finding is that while integrating PP and CP within the application of coaching gains momentum in the academic community, ‘on the ground,’ the fields of PP and CP were understood and operationalized as separate and distinct fields. Participants had varying awareness and understanding of the utilization and application of PP, CP, and PPC.

The second main finding is that participants did not utilize all six elements of Burke’s Conceptual Framework (2018), such as having an in-depth knowledge of both PP and CP, using positive diagnosis for peak performance, using Positive Psychology Interventions, and utilizing positive scales and measures. This was due, in part, to preferences, lack of awareness, or lack of training. Therefore, according to Burke’s (2018) Conceptual Framework, the participants in this research study had not fully integrated PP within their coaching practice and maximized its full potential.

The consequences of this are that the coaches did not identify themselves as positive psychology coaches using instead their niche area to explain to clients their area of practice.

The third main finding is that participants value the science of PP and grounding their coaching practice in evidence-based research with greater integration into coaching psychology approaches and outcomes. They also valued further education, training and credentialing to fully practice and apply an integrated approach to Positive Psychology Coaching in their coaching.

The findings and theoretical codes led to the construction of the Foundational Training Model for an Integrated Positive Psychology Coaching Practice (see Figure 2), which underscores the importance of combining evidence-based practice, professional training and certification as the solution to guide coaches to practicing PPC in a focused, integrated and cohesive way.

This study clarifies an under-researched area of the current state of practicing positive psychology coaching ‘on the ground’ with credentialed coaches who self-identify using positive psychology in their coaching practice. It also advances the knowledge and provides researchers, educators, and practitioners with guidance to inform future training, thereby enabling credentialed coaches to practice PPC effectively in this emerging integrated field.

Authors

Meriflor Toneatto is an award-winning, multi-passionate executive with 28 years of leadership, coaching, mentoring, and entrepreneurial experience. She is the founder and CEO of the Institute of Positive Psychology Coaching (IPPC), a global virtual institute dedicated to training, education and certification in the emerging field of applied positive psychology coaching.

Founding the IPPC is an extension of Meriflor’s desire to address a gap in providing high-quality, evidence-based training for professional coaches and contribute to the advancement of the coaching profession with the motto to ‘Do Good & Prosper.’

After a 15-year leadership career in the public sector, during which she was involved in major policy initiatives for social impact, human rights, health and cultural preservation, Meriflor shifted her focus to her passion: coaching and transforming lives.

Her coaching experience spans a diverse audience and industries, from executive, leadership, personal, business, entrepreneurial, and book coaching/publishing to women’s empowerment.

She holds a BA in Public Administration and Public Policy from Toronto Metropolitan University and an MSc. in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology (MAPPCP) from the University of East London. She is a Doctoral candidate at Middlesex University with a transdisciplinary research focus on positive psychology coaching and leadership development. She is also a Master Certified Coach (MCC) with the International Coach Federation.

Meriflor is the recipient of the prestigious Amethyst Award for Excellence and Outstanding Achievement from the Government of Ontario, Canada.

Dr. Alison Bishop is a lecturer on the Master in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology degree at the University of East London. Prior to that, she lectured in the Childhood department at the University of Suffolk for over three years, teaching a variety of modules related to the psychology and sociology of childhood.

She has an interest in special needs, in particular, autism spectrum disorders. She also has experience in play therapy for children with autism, having worked in a number of different education settings in the past. Alison is also a counsellor and a coach and so brings a therapeutic approach to all she does.

Alison completed her undergraduate degree at The University of Suffolk, graduating with a 1st class honours and a prize for her research dissertation. She then went on to gain a distinction in her Master’s at the University of East London in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching – the degree course that she now teaches.

She was awarded her Ph.D. from the University of East Anglia, where she researched resilience experiences in mothers of children with autism. This research created two conceptual frameworks for resilience, the resilience cycle and the resilience signature, which provide a kinder, more inclusive narrative around this topic.

In her spare time, Alison enjoys playing the piano and trumpet. She also enjoys walks by the coast with her little dog, Hugo.

ORCID number: 0000-0002-0972-1686

Dr. Sok-ho Trinh is a British and French-born Chinese executive coach, academic, entrepreneur, Passionologist, corporate leader, and professional actor-performer.

As a Passionologist, he investigates passion at work, leader and employee engagement, positive leadership, well-being in the workplace, and well-being and performing arts.

As a practitioner, aka Dr. Passion, Sok-ho provides leadership development and coaching to leaders, teams, and entrepreneurs globally. As a business leader, he served global organizations in retail and consumer analytics and data science. As an academic, Sok-ho leads an MSc in Strategic Leadership. He has been teaching Leadership, occupational psychology, and positive psychology.

Sok-ho is a professionally trained artist who has worked in musical theatre, screen acting, and voice acting.

Sok-ho holds a BSc, an MSc, an MBA, a CPCC, a PCC, a PGCE, a diploma in Acting, an FHEA, a PhD in positive psychology and leadership, and certifications in mindfulness, psychometrics and LegoSeriousPlay®.

Sok-ho was born in France and raised by Chinese parents born in Cambodia. He can speak eight languages, has lived on three continents, and is now based in London, UK, with his family.

His motto in life is Live with Purpose and Passion.

ORCID number: 0000-0001-6662-1406