Introduction

Today’s leaders have rigorous job demands, including holding multiple roles, having intense traveling schedules, managing large teams and productivity, and navigating an ever-changing corporate culture, while monitoring the bigger picture. Personal well-being may be challenging to incorporate into the lives of those with limited time and high demands. Within the past few years, burnout has increased dramatically among leaders and their teams. In fact, the World Health Organization has labelled burnout an ‘occupational phenomenon,’ indicating that burnout is not just an individual issue—it is related to the workplace environment and conditions (Mckinsey & Company, 2023; World Health Organization, 2019). Stress impairs access to brain areas used for innovation, creativity, and awareness of broader perspectives necessary to flourish within the workplace (Valeras, 2020; Wang et al., 2019). However, for optimal living, human flourishing is paramount for leaders to perform at their best and meet demands like creativity, innovation, and fiscal performance (Seligman, 2011).

Since human flourishing encompasses all aspects of life and the human condition, the ability to measure this is important to evaluate individual well-being. The PERMA model (Seligman, 2011) exemplifies the concept by proposing five pillars of human flourishing, including: Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationship, Meaning, and Accomplishment. Dr. Kern (2020) added the H for health, implementing the PERMAH model in schools with Seligman’s permission (Kern, 2020). Evidence supports that the arts and humanities can increase human flourishing, regardless of age (Tay & Pawelski, 2022). Arts in particular the field considered in this study, can evoke positive emotions, increase life engagement, enhance intrinsic motivation, broaden perspective, and improve overall well-being (Darewych, 2022). D’Olimpio (2022) found that creative arts experience induces sensations, feelings, and thoughts, both cognitive and emotive. In addition, the arts encourage meaningful engagement and eudemonia by connecting cognition with affect and somatic awareness, which are included in the human experience (D’Olimpio, 2022; Lamont, 2021; Tay & Pawelski, 2022). As cited in Wright and Pascoe (2015) the highly regarded artist, Henry Moore aptly described this, "‘Art is not to do with the practical side of making a living. It is to live a fuller human life.’ "(p.296)

Research suggests that the arts allow people to find meaning and purpose. For example, Lamont (2011) and Packer & Ballantyne (2011) found that festival and concertgoers reported experiencing a more profound sense of purpose and identity by attending these events. Other research studies suggest that older adults use the arts to express and reflect on life experiences; as a result, they were more engaged and derived meaning from life experiences (Bradfield, 2021). Through reflection, insights are gained, whether through creating art or attending concerts; this further demonstrates the link between the arts in meaning and engagement. Leaders with positive well-being, meaning, and purpose positively influence their teams (Gladis & Goldsmith, 2013). It is also true that meaningful work contributes to better engagement, job satisfaction, commitment, and psychological well-being (Lips-Wiersma et al., 2022).

Studies indicate that relationships and connections can be improved through the arts. For example, when leaders were given an art-based intervention compared to conventional leadership development training at work, they significantly increased prosocial behavior (Romanowska et al., 2013). The most common complaint among leaders is that it is lonely at the top, indicating that relationship development is a necessary component in leadership roles, particularly as a key component of human flourishing (Seligman, 2011). What if, through daily art practice, more relationships could form, and deeper connections could be made? For example engaging in music and theater can improve empathy, an essential component of interpersonal connection and relationships (Lamont, 2011; Walsh, 2012). The arts have also benefitted the revitalization and building of communities (Hetland & Kelley, 2021) and building a generative community is like managing teams that rely on healthy relationships, thus encouraging human flourishing (Adler, 2006).

Concerning health, could it be that an art intervention each day could keep the doctor away? There is evidence that practicing arts may have health benefits. Studies have observed decreases in cortisol levels when participants listen to music (Christopher et al., 2016; Khalfa et al., 2003). Similarly, expressive writing is reported to decrease chronic stress, increase optimism, and mitigate feelings inspired by a stressful event (Mackenzie et al., 2008). Moreover, stress reduction through experiencing the arts could build resilience to rigorous demands and create healthier leaders (Khalfa et al., 2003).

Positive outcomes for overall psychological well-being can be achieved through the arts (Croom, 2015). Studies of experiencing, consuming, and playing music have found correlations between music benefits and human flourishing, life satisfaction, and well-being (Croom, 2015; Krause et al., 2020; Lamont, 2021; Ritter & Ferguson, 2017). Specifically, an art intervention of visual journaling was performed to help medical students cope with stress, and participants experienced a decrease in anxiety (Croom, 2015). Over the past decade, art therapists, knowing the benefits of art on psychological well-being, have integrated positive psychology and the PERMA model into practice (Chilton, 2017). The following section explores current and past research on the relationship between the arts, human flourishing, and leadership.

“The arts aim to represent not the outward appearance of things but the inward significance”.

-Aristotle

Engaging the in the Arts

The creative arts encompass activities such as painting, dancing, music, sculpting, and literature. On the other hand, the arts and humanities have a broader scope, including philosophy, ethics, history, and religious texts (Tay & Pawelski, 2022). This wider arts and humanities perspective allows for exploration and expression, promoting the development of critical, creative, adaptable, and independent thinking (Vaziri & Bradburn, 2022). These skills are particularly valuable in leadership (Hemlin & Olsson, 2011; Rodgers et al., 2010). Identifying the factors that influence individuals’ engagement in the arts can facilitate the design of studies that account for these variables. For example, there are various factors to consider based on who and how people have been exposed to arts and humanities. These factors influence their relationship with the arts and how they engage with them (Shim, 2021). Variables that affect how we engage with the arts, such as adaptability, require cognitive flexibility. This can be enhanced through participation in the creative process. This, in turn, facilitates a deeper awareness and broadening of perspectives (Fredrickson, 2001; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). From a broader perspective, engaging in the arts can promote social connectivity and meaning-making, which are significant to human flourishing and are pertinent to leadership because higher quality relationship exchanges with trust and openness have positive work-related outcomes, including better job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and performance (Dulebohn et al., 2012). The arts can be experienced through creating, experiencing, or appreciating art (Kou et al., 2020; Shim, 2021; Tay et al., 2018). Table 1 presents modes of engagement in art alongside findings on how these can improve psychological well-being.

Many of the studies presented in Table 1 utilized small sample sizes, potentially limiting the generalizability of their findings. However, existing research provides a foundation for exploring the potential psychological effects of the creative arts. While engaging in the arts is relatively safe, some individuals may feel uncomfortable due to fear and vulnerability. When engaging in creative expression, it is important to know that accessing past traumas may trigger intense emotions that could be overwhelming. Therefore, it is critical to understand these risks to create a safe and supportive environment.

Measuring arts and humanities and human flourishing

When exploring potential outcomes of the arts and humanities and human flourishing, it is essential to recognize the shortcomings and possible biases related to evaluative tools. Most measurement scales are subjective and can influence mood when completing a questionnaire (Tay & Pawelski, 2022).

Tay et al. (2018) developed a seminal conceptual framework for the role of arts and humanities in the human flourishing model that defines subjective modalities, recognizes how art is engaged, and identifies the components of human flourishing. This conceptual model identifies how we engage in the arts and consists of four categories, namely, immersion, embeddedness, socialization, and reflection.

Immersion is described as being fully absorbed in a modality like dance or music, often losing track of time and exhibiting positive physiological and psychological reactions (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014; Tay et al., 2018). Embeddedness is developing skills through the arts, evoking a sense of mastery or self-efficacy (Deci et al., 2017; Malchiodi, 2003). Socialization is discovering roles or identities in a community or culture based on exposure to the arts and promoting pro-social behaviors (Lamont, 2011; Tay et al., 2018). Reflectiveness is gaining new insights or perspectives through art engagement. Reflection can also promote discoveries in meaning and purpose (Tay et al., 2018).

Human flourishing and the arts

The pillars of human flourishing are described within the PERMA framework are Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationship, Meaning, and Accomplishment (Seligman, 2011). This framework has been adapted to include H for Health, physical health, activity, sleep, and nutrition. Table 2 presents a comprehensive description of the PERMAH framework and its relationship with arts and humanities, including how they are (Seligman, 2011; Suldo, et al., 2022)

Human flourishing can be achieved by experiencing growth in the six categories included in the PERMAH framework (Horsfall & Titchen, 2009; Kern, 2020). For example, playing in an orchestra or band involves listening to music, including positive emotions such as awe and contentment, and increases cognitive skills for engagement and flow (Lamont, 2021). Visiting a concert or museum, art making, dancing, and engaging in literature can boost your sense of belonging and purpose, which are included in relationships and meaning; at the same time, the arts can reduce cortisol levels, improving one’s health (Cotter & Pawelski, 2022; Hui et al., 2009; Lamont, 2011; Lupien et al., 1998; Malchiodi, 2002). By recognizing the alignment between the arts and humanities and the PERMAH, further research can explore the potential impact of the arts on optimal living, which would benefit leaders with significant job demands (Keyes, 2002).

Leadership

Leaders face the challenge of balancing the demands of effective leadership with the competing priorities of organizational productivity and limited resources and time while maintaining a creative mindset (Černe et al., 2013; Ritter & Ferguson, 2017; Runco, 2021). Leaders with high-demand roles and limited time often need to proactively support their well-being, which can produce a healthier workplace and team (K. Cameron & Plews, 2012; Seppälä & Cameron, 2015). Positive leadership aims to empower employees by achieving meaning and purpose, building relationships, and assuring a safe work climate, which interrelates with the PERMA model through all five pillars (K. S. Cameron, 2012; Gauthier, 2015; Malinga et al., 2019).

A creative arts practice can improve resilience and prosocial behavior among leaders (Romanowska et al., 2013). Authentic leaders’ traits and behavior, such as transparency, influence innovation and creativity at the team level, creating trust and psychological safety through better prosocial behavior (Chow, 2017). This allows team members to feel more open to sharing novel ideas, contributing to workplace innovation (Černe et al., 2013).

Leadership today can be described as an art rather than a science (Rodgers et al., 2010). For example, Israeli music conductor, Itay Talgram, uses an orchestra metaphor for authentic leadership (Kumar, 2011). He believes the workplace culture, like an orchestra, begins with the leader, the conductor. They create psychological safety by engaging with each individual and letting members know their purpose or impact (Kumar, 2011). Each instrument or person is an integral part of a larger community, establishing connection and engagement among the orchestra while creating beautiful music (Kumar, 2011). Being part of something bigger, like an orchestra, is an example of meaning (Kumar, 2011; Romanowska et al., 2013).

Through being part of a larger entity, like a corporation, a leader’s adaptability is essential in adjusting to change, evident in today’s market (Rosing et al., 2011). When positive emotions are induced, people become more creative, develop more cognitive flexibility, and become more adaptable (Fredrickson, 1998). These positive emotions have a bidirectional relationship with creativity (Tan et al., 2021). Since creativity begets more creative ideas, this assists in developing divergent thought, which helps leaders think outside the box, allowing for growth within teams and organizations (Ritter & Ferguson, 2017; Runco, 2021; Snyder et al., 2020). Moreover, the creative process encourages intrinsic motivation, or balancing liking and being challenged by a task (Vrooman et al., 2021). This promotes efficacy and autonomy associated with positive meaning and flourishing within organizations and improves the individual’s overall well-being (K. S. Cameron & Spreitzer, 2013; Vaziri & Bradburn, 2022).

Study aims

Previous art studies related to human flourishing revealed a gap in research primarily related to those in leadership roles. Creativity is desirable among leaders, but more evidence of its development is needed (Adler, 2006; Rodgers et al., 2010). The extant studies on arts and humanities, human flourishing, and leadership provide a foundation for the present work: exploring different themes related to those in leadership roles through a 21-day creative arts intervention. This research seeks to answer the following question: ‘What are the lived experiences of leaders engaging in a 21-day daily creative arts intervention.’

Methodology

Design

During the 21-day creative arts intervention, participants were provided with a variety of prompts, inviting them to engage in activities related to literature and poetry reading, music reflection, fine arts, online improv, and virtual museum links. The time required for these activities varied from five to over twenty minutes. The prompts were intended to facilitate their engagement with the arts, encouraging the exploration of ideas not included in the list. Table 4.2 shows examples of the art forms selected by the participants.

As leaders have limited time, the 21-day period was chosen to reduce study dropouts while allowing meaningful data collection. Over the course of three weeks, participants will be able to explore a variety of art modalities. In a study on habit formation, three weeks is a suitable time to develop and strengthen healthy habits. (Mergelsberg et al., 2021). If desired, this study could serve as a springboard for continuing arts practice.

To explore the experiences resulting from the intervention, this epistemological qualitative study collected data via semi-structured interviews of thirteen leaders post-intervention, which were subjected to thematic analysis. Reflexive thematic analysis was utilized to maintain flexibility through exploration of the leader’s experiences, allowing for proximity to the subjects and data while keeping a reflexive journal to record any thoughts and feelings, as well as illuminating potential personal biases about the experience. Aspects of template analysis style were used within the thematic analysis, whereby coding is hierarchical, while flexibility allows for adaptability to study needs while maintaining a high degree of structure. (Brooks & King, 2014). Then, the template was applied to the data, and codes were created and funnelled from the bottom up to develop the themes and sub-themes for this study (Braun & Clarke, 2021; Brooks & King, 2014).

Sampling and recruitment

Purposive convenience sampling was employed to recruit a diverse group of leaders since they were accessible within the researcher’s personal network (Clarke & Braun, 2013). Using purposive sampling instead of random sampling allowed for familiarity with the participants, for in-depth conversations. Table 3 provides a detailed demographic breakdown of participants.

The anonymized participants listed in Table 3 reside in the United States or Switzerland and range in age from 38–65 years old. Professional leaders were selected as the population; all participants held advanced degrees. The participants were distributed across various industries and roles, including government, military, pharmaceutical, health care, engineering, and C-suite executives. The table excludes specific details regarding each person’s industry affiliation to maintain anonymity.

Procedure & data collection

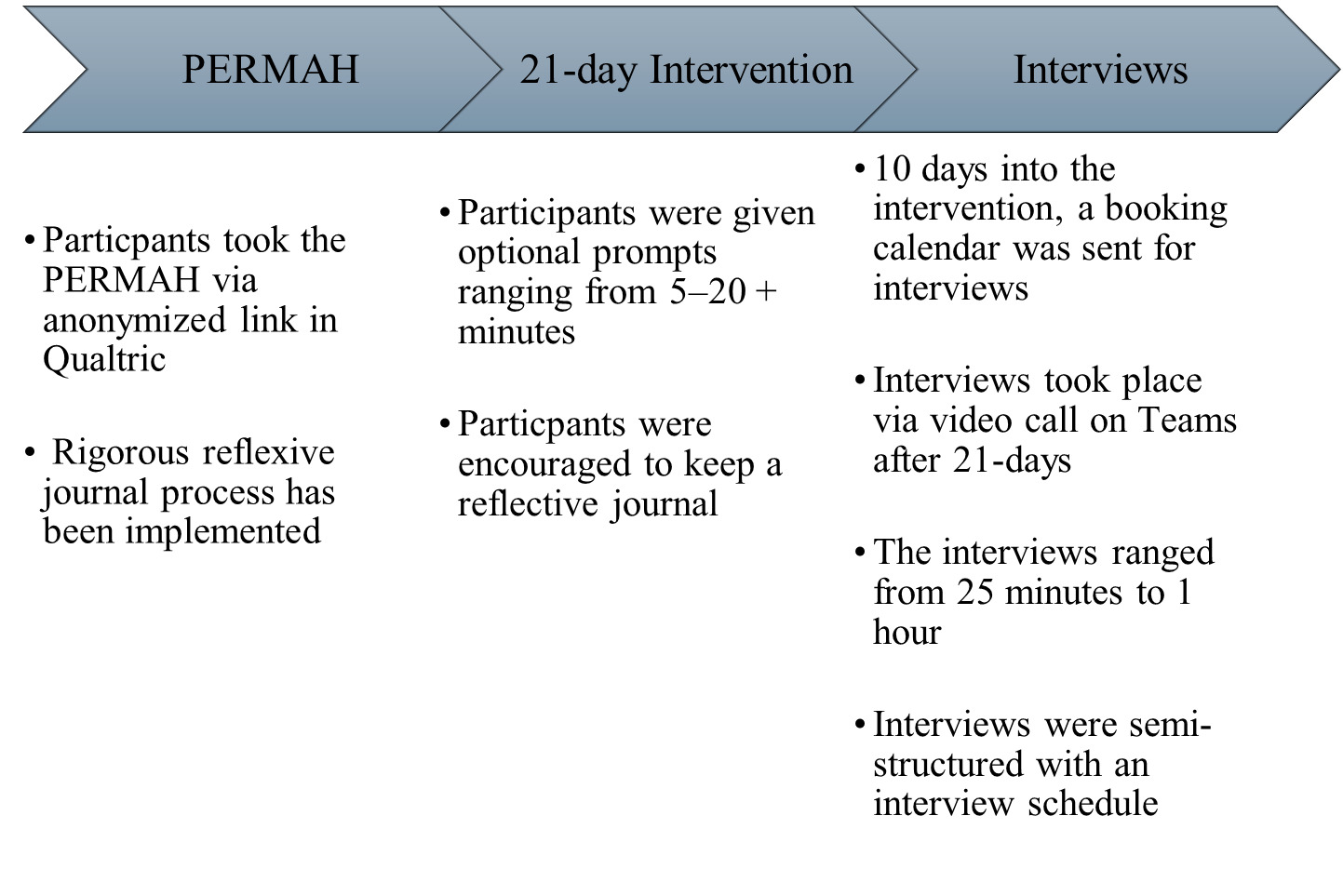

Data collection was conducted following the guidance of Creswell and Poth (2018). A PERMAH questionnaire was implemented at the start of the study. The purpose was to familiarize the participant with the well-being language and to begin a reflective process (Butler & Kern, 2016; Creswell & Poth, 2018). Interviews were used to explore and initiate in-depth conversations about the participants’ lived experiences and to identify themes related to the research question and other unanticipated themes (Braun & Clarke, 2021). A detailed flow of data collection is shown in Figure 1.

The interview schedule began with a set of questions related to the research question and previous research from the literature review. The questions included their experience or exposure to the arts, which creative arts they selected, and how they perceived their well-being inside and outside work. Because this was a reflexive thematic analysis, maintaining a lens of openness, awareness, and curiosity were necessary to gather the lived experience of the leaders (Braun & Clarke, 2019). This was demonstrated in the interview question, “Are there any questions that were not asked that should be included?” This question resulted in a few additional questions that were subsequently added to the interview schedule (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Data analysis

The transcribed interviews were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis, and Braun and Clarke’s (2021) six-phase process were followed, which includes familiarizing, coding, and generating initial themes, developing and reviewing themes, refining/defining themes, and writing up. The coding accounted for an organic and evolving process, working from the ground up. Based on the interview schedule, prominent themes emerged; therefore, aspects of template analysis style were used within the thematic analysis, a typical theme used in a top-down approach (Brooks & King, 2014). The template was then applied to the data, and codes were created and funnelled from the bottom up to develop the themes and sub-themes for this study (Braun & Clarke, 2021; Brooks & King, 2014).

The four a priori themes were identified from the interviews and interview questions, and coding was then shifted back to the bottom-up approach (Brooks & King, 2014). The combination of funnelling down and working from the bottom up illuminated the alignment of the PERMAH sub-theme (Mayer, 2019).

The codes shifted slightly based on clarity and noticing similarities in the subjects’ experiences. This audit trail of generating, refining, and reviewing codes further pointed to additional sub-themes, for example, resilience was identified during a second round (Braun & Clarke, 2021). From the coding, the themes were mapped out on posters. The themes were reviewed several times, participants were matched to the themes with a tally system, and quotes were included to provide more evidence. The reflexive journal was reviewed to observe additional insights. Data collection and extensive analysis confirmed that themes and sub-themes aligned. Lastly, the write-up of themes was initiated, and a detailed table was created with quotes from all participants related to the given themes (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Successful data collection and analysis occurred through maintaining proximity to the data and participants coupled with a flexible interpretive approach using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

Results

Four themes were identified: previous exposure to the arts, creative arts practice, well-being, and leadership. These themes, along with the subthemes, are presented in Table 4, which includes illustrative quotes to provide evidence of the relevant

Previous exposure to the arts

‘My father said, “Never sing, you get everyone off (tune)”’ (Donna). This theme represents the lens through which participants viewed creativity or their relationship to the arts before the 21 days. This was relevant because the participants’ past exposure to the arts set the tone for how they initially experienced the 21 days. One mentioned, ‘I was skeptical’ (Sarah), while another said, ‘I used to do art as a child’ (Dan). These quotations illustrate the varied past exposure experienced by the participants.

Arts and creativity defined

This sub-theme further described relationships with the arts, defining individual perceptions of creativity. Becky said, ‘a creative person comes up with new ideas and ways of doing things.’ Similarly, Donna felt ‘creativity was looking at different approaches.’ Looking through the character strength lens, Jennifer mentioned that ‘creativity is one of my values.’ Defining the arts and creativity for the participants illuminated how past perceptions included production value versus being novel or innovative in the workplace. It sparked discussions of personal shifts in perspective over the 21 days. Becky mentioned, ‘I am not an artist; I don’t have skills. I don’t have to be Van Gogh; I am doing it for the process that is something I would not have known about myself before.’ Emma found it was ‘a nice way to bring me back to what I love about the arts,’ which, for her, was activism.

This sub-theme illustrated the subjective and complex nature of the arts and creativity, as it evoked a wide range of perceptions based on experience with the arts, ‘the systemic kind of devaluing of the arts as a product of society, I feel I have embodied’ (Emma). Interestingly, the engagement in the arts and the interview discussion broadened the perspective around how they define the arts, shaped by past experiences.

Past experiences shaped perception

Each participant organically shifted toward their childhood experience. Each perspective was unique, ranging from ‘since I was tiny, I have loved art’ (Jennifer) to ‘my father made it clear that I was an idiot when it came to music; I always shied away’ (Donna). From a philosophical perspective, Emma recognized that she was ‘de-incentivized to go towards arts’ because she felt it was about the production value and ‘not art for art’s sake,’ negatively impacting her relationship with the arts. This theme includes negative and positive associations, illuminating art as a process versus the value placed on an outcome or product.

Perceived ability

Perceived ability is how the participants viewed their artistic skills. The participants’ perceived abilities varied from ‘identifying as an artist’ (Renee) or ‘I mostly appreciate the arts’ (Emma) to ‘I can’t draw a straight line’ (Lenia) to ‘Nannies did the crafts with my kids because they would not get that from me’ (Sarah). The participants shared, without prompting, their skills and deficits within the various modalities; their perceived skills influenced how and what they chose to engage in the arts, i.e., as an appreciator or consumer versus artmaking.

Creative arts practice

‘Just looking at her work reminds me of the possibility of art and that there’s no limitation in creativity’ (Jennifer). While past exposures and experiences differed, so did what, how, and when the participants engaged in a creative art practice. Because of this complexity, four sub-themes emerged: duration, implementation, activity, and overall experience.

Duration

The theme duration and timing of engagement refer to how many of the 21 days they logged, time of day, and the session length. Most participated in over 75% of the 21 days, engaging from five minutes to an hour, with occasional longer sessions. Tara said, ‘I only missed one (day) because I had a checklist.’ Most engaged in the morning before work, at the end of the day, or during a midday break, ‘I wrote for twenty minutes and made up a story about a green sofa’ (Jennifer). This means that the leaders were committed to the study, engaging in most of the 21 days.

Implementation

Because of the leader’s participation, their consistent adherence likely resulted from how they implemented the intervention, whereby most scheduled the intervention, ‘I traveled 3 times in the last 21-days, no matter where you go, you can make it part of routine, you can bring music with you’ (Yvonne). Implementation included getting started, any resistance described, and the processes during and after the intervention. Getting started was challenging for some participants. Lenia stated the ‘beginning is not easy.’ A few were met with some resistance; Emma stated, ‘I didn’t want to do it when it felt like it was one of those chores.’

Others found it easy when it was placed in their calendars; Tara created a checklist, and Chris set a reminder. For Sarah, Yvonne, and Dan, it became a routine. It was unanimous that all participants intended to continue with the art practice. For Lenia, ‘The incentive (to continue) is that I feel good.’ This means that once they began, they experienced benefits and enjoyment in the process, intending to continue beyond 21 days.

Activity

This sub-theme relates to the types of activities selected during the intervention. Collectively, they engaged in most modalities; some chose to be art consumers through visits to art galleries, reading literature, or listening to music, while others chose to engage in artmaking through collaging, photography, dancing, and music. Each participant uniquely engaged in the arts. For example, Kathy said, ‘I made a 21-day playlist,’ Becky said, ‘I did a scribble and would color it in,’ Donna said, 'I go to ballroom dancing," Chris said, ‘I play the piano and trumpet.’ Both Dan and Renee said, ‘I would see something beautiful and take a picture of it.’ This illustrates the eclectic selection of the arts chosen by the participants. The participant-driven activity selection meant that there was something for everyone within their comfort level. The illustrations below are examples of art created by participants.

Overall experience

Overall experience refers to the key insights reported by the participants. The reflective nature of the arts provided many outcomes and recognized benefits for the participants. Stephanie found the importance of a creative break, ‘pausing to do things that really bring me joy at the moment has a long-lasting benefit.’ Similarly, Sarah said, ‘It was a proper wind-down; it makes a difference (for your) overall psyche.’ Yvonne concurred that ‘it is something you do not have to put much time or thought into, but it can have a good payoff for really no investment.’ Donna experienced a positive shift, connecting music to her love for dance: ‘dancing to me was physical, I never thought of dancing as music.’ This means that the overall engagement experience is individual and related to their past exposure. Participants mentioned that through the reflective nature of the arts, they gained new insight or perspective. This is further expanded in the following master theme: well-being.

Well-being

‘I just really enjoy that kind of fun, let’s start the day off on a positive note’ (Yvonne).

Through the creative arts, well-being emerged as an expansive master theme. Joy and better sleep were the first codes; from that, all the PERMAH pillars became evident, thus becoming a sub-theme. Many leaders had challenges either with work or in their personal lives, such as loss or travel. Dan, for example, said, ‘during these 21-days I have been in six states.’ Finally, resilience was identified as a sub-theme, as the arts provided better coping and increased stamina; these are presented below.

PERMAH

The PERMAH sub-theme includes all six pillars of human flourishing, which were all evident throughout the data. Because of the amount of data supporting well-being in the study, this section provides a snapshot of the material that will be further discussed in the subsequent section. All participants experienced positive emotions; for example, Yvonne experienced both a release and joy, ‘I love to sing, it was not just distracting, but joyful, that feeling of just letting loose.’ Similarly, Lenia stated, ‘I am feeling more relaxed. I am feeling more peaceful.’ Words like ‘playful,’ ‘curiosity,’ and ‘awe’ were mentioned throughout the interviews.

There was evidence of health and behavior changes. For example, Stephanie and Lenia said they slept better and felt more refreshed. Another lifestyle change was Yvonne exchanging her wine glass for art in the evening. Lenia, Kathy, and Sarah exchanged TV for music listening because it made them feel relaxed. Many increased physical activities by using dance in the intervention.

The relationship pillar unexpectedly took center stage among sub-themes. The intervention became a shared experience through the inclusion of family or co-workers in the art, ‘I enjoyed when we’re together as a family, finding joy in the moment together’ (Stephanie). Several participants described themselves as more open, friendly, and outgoing. Donna reported, ‘(I am) a bit more extroverted than I usually am; I am more playful.’

In this study, engagement, meaning, and accomplishment were all evident. Chris engaged in music, stating, ‘I was investigating new things I had never heard before,’ and Becky felt a sense of pride from the outcomes of artmaking. Jennifer felt a deep sense of meaning as she listened to John Coltrane’s My Favorite Things and reflected on her favourite things. The data revealed increases in all six pillars of human flourishing across the entire sample. The findings support that the creative arts intervention improved well-being, regardless of the selected modality.

Challenges and transitions

Challenges and transitions represent obstacles the participants mentioned during the interview that may impede well-being. The participants experienced heavy workloads, and many were balancing that with family life. Chris mentioned, ‘for about two weeks (during the study), it was just nonstop stuff with them (the kids) and then my work.’ It was an international move for Sarah with her family, who ‘were still trying to get settled.’ Understanding these challenges offers insight into potential stressors experienced during the intervention. The following section demonstrates how the arts contributed to the participants’ resilience during their challenges.

Resilience

Resilience, in this study, is defined by better coping, increased stamina, and optimism throughout the intervention. For example, Lenia stated, ‘it (the arts) helped navigate me through a little bit of a rough time.’ For Becky, Jennifer, Yvonne, and Sarah, the intervention helped ‘give a mental break,’ ‘see the bigger picture,’ and be ‘ready to tackle what is next.’ Thus, the arts can provide an opportunity for a reprieve during challenging times, ultimately fostering strength among participants.

Leadership

‘I noticed we (the team) are in harmony’ (Chris).

Leadership encompasses all aspects of being a leader, from job demands, organizational challenges or workload, and their perceived role, including a ‘bigger picture’ perspective, teaming, and productivity. Dedication to their work and striving to be better for the teams they support were evident among these leaders. This section depicts their experiences and noticeable shifts during the intervention.

Job demands

Job demands are defined as team challenges, workload, and organizational changes, as most participants who work within corporations or systems experience change. A notable challenge was supporting the team while being aware of self-preservation. Several participants had heavy travel schedules, carried two roles through a transition, or had ‘an accumulation of too many projects.’ Through these challenges, they produced deliverables while monitoring the bigger picture. For those running corporations, the harsh reality of well-being in the workplace is ‘we’re making money, or we’re not.’ Thus, leaders are aware of the pressure to produce while feeling an immense responsibility to care for their teams.

Outcomes

The outcomes, or noticeable shifts, that participants experienced during the intervention included a broadening of perspectives, teaming, and productivity. Some found a direct correlation to the arts, while others observed these changes but were uncertain about a correlation. Sarah ‘listened to Release (Pearl Jam) three times and started to feel in touch with that bigger picture of the top strategic issue.’ This helped give her the space to gain a new perspective. Jennifer said she ‘needs creativity to stay adaptive in her leadership.’ Kathy feels that as a leader, ‘when I feel good, I can uplift and inspire.’ She also started a work hour implementing background music for her team, noting that ‘people seem to be a whole lot more productive.’ Several others noticed changes in their relationships with their colleagues and an increase in team cohesion and productivity. Lenia stated she ‘is working less’ but is ‘more effective and more concentrated’ because of the intervention. The following quote from Renee demonstrates her ‘lived experience’ utilizing the arts during the intervention and how it relates to her leadership productivity, perspective, and teaming necessary for her role:

This (the arts) connected in a team building sort of way, coincidentally or perhaps as a result of that emotional safety or being in touch with yourself, I have created our team meeting, and it has synergized everybody. There is so much more connectedness. It is a really good lens to bring about positive change, camaraderie, teamwork, and ultimately impact because we are producing better and more purposeful deliverables.

Thus, the leaders noticed positive work-life changes during the intervention. It is plausible that it could be related to the intervention.

Discussion

Many participants in this study described a release following their creative experience. According to existing research, listening to or performing music can relieve stress and promote feelings of well-being (Shim, 2021). Participants also found the experience calming and peaceful, supporting the findings of Malchiodi (2003), who reported that art-making had been shown to provide stress reduction, a sense of calm, and centering.

Participants in this study noted finding a sense of meaning and connection when experiencing live music, mirroring findings from previous studies showing that people attending live performances experienced increased meaning and engagement, whereby human connection, a sense of identity, and purpose are felt (Lamont, 2011; Packer & Ballantyne, 2011). Furthermore, engaging in live music could improve some aspects of leadership, including purpose and relationships, as suggested by a participant in this study who was inspired by a live performance to recognize leadership qualities upon self-reflection.

The creative arts helped to increase positive emotions, and the positive emotions provided more opportunities for creativity (Figure 3). For example, one participant practiced arts that boosted her positive emotions, which then increased her creativity throughout the day.

In the reflexive journal, it was noted that during the interviews, participants displayed positive changes in energy when describing their experiences. This energy shift led to creativity being expressed using metaphors. For example, one participant related life experiences to a Charles Dickens novel, while another connected with the movie The Last Samurai in experiencing beauty and finding hope. Consistent with the literature, Figure 3 illustrates that a bidirectional relationship of creativity and positive emotions relates to Fredrickson’s broaden and build theory (2001) and upward spirals (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018), whereby positive emotions increase creativity. Creativity, then, increases positive emotions (Fredrickson, 2001). This further demonstrates the relationship between positive emotions, creativity, and the arts impacting human flourishing.

Engagement and flow were experienced by most participants. For example, the experience of exploring new content while playing musical instruments led one participant to feel a sense of fulfillment. Related to the literature, the right amount of challenge to meet a person’s skill level often induces flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Additionally, losing time and getting lost in an activity are correlated with flow, which was reflected by participants in this study who were able to experience losing themselves in the awe of talent and finding that time flew by during active art participation that was enjoyable. This finding is consistent with research on time loss being an early indicator of the flow state; there is a loss of self-awareness during the down-regulation process (Kotler et al., 2022).

Engagement and flow are important for leaders because they provide enjoyment, allowing the subconscious to enter the conscious, which broadens perspectives, ultimately leading to clarity (Vrooman et al., 2021). Getting into a relaxed state to see from a broader perspective takes time, which is limited for leaders. When work is at its most challenging, the prefrontal cortex and amygdala are triggered by the fight or flight response, making it challenging to utilize the parts of the brain necessary for critical decision-making, social cognition, and seeing the bigger picture (Gupta et al., 2011). This finding supports the notion that music can mitigate stress, facilitating a shift from survival mode to obtaining the space to gain perspective, further demonstrating how the arts could contribute to human flourishing in leadership—it is challenging to engage in the arts when in survival mode, providing the two-fold benefits of downregulation and perspective.

Health and lifestyle changes, including better sleep, a decrease in alcohol intake, more physical activity, and diet changes for many participants, were intriguing findings. Moreover, lifestyle changes were initiated by multiple participants during the intervention. Several participants replaced TV and media with music, writing, or coloring, and one participant found that coloring served as a distraction from the urge to consume alcohol. Many participants increased physical activity by dancing during the 21 days. The reflective process could explain these health benefits and the stress reduction associated with the intervention, and the process of daily repetition could have influenced health.

This is congruent with findings on decreased cortisol levels and health benefits when engaging in mindfulness-based activities like music, as mentioned earlier (Christopher et al., 2016; Khalfa et al., 2003). It is understandable how a decrease in cortisol can have many health benefits and that the arts have many psychological benefits contributing to overall health (Malchiodi, 2002). What seems different about the present findings compared with those from previous research is the observed changes in health habits and the adoption of a healthier lifestyle throughout the intervention. The reflective process may have provided awareness of the participants’ habits. Another possible explanation is that positive emotions provided increased motivation. These findings lay a foundation for future exploration of the possible contributing factors and explanations for the lifestyle changes that were observed.

Self-mastery, self-efficacy, increased confidence, and fulfillment were encouraging findings. Participants leaned into their inquisitive nature, e.g., by learning new music or studying architecture, leading to a sense of mastery and fulfillment. On the other hand, one participant mentioned feeling frustrated by the outcome of one of their drawings when recalling past experiences with art and production value, which created emotions of disappointment and self-critical thoughts. This experience led the participant to reflect on the process, resulting in the insight that she preferred her other styles. These findings mirror results from previous research—the arts provide obstacles and opportunities for problem-solving but can also produce frustration and disappointment in the process (Bayles & Orland, 2001). A sense of achievement and satisfaction can be provided through engaging in the arts (Clift et al., 2015). Research suggests that being deeply engaged in art invokes curiosity and problem-solving, often resulting in a sense of accomplishment (Patterson & Perlstein, 2011).

This study aimed to explore leaders’ experiences participating in an art intervention, hoping that they might experience some elements of human flourishing. It is notable that participants’ relationships and team interactions significantly improved during the intervention. This is consistent with previous findings that arts-based interventions can improve social connections (Romanowska et al., 2013) To my knowledge, this is the only study of leaders participating in a creative arts 21-day intervention; therefore, some outcomes are expectedly unique to this experience. For example, working with a diverse global team and integrating creativity into team meetings helped one participant create cohesion. Given that art is a universal language, this was particularly important for that team, which was comprised of members from diverse cultures. The arts helped the participant feel more confident, resulting in their team appreciating the authenticity they sensed and providing positive feedback. While some similarities could be drawn to the research of Romanowska et al. (2013) whereby leaders demonstrated improvements in resilience and prosocial behavior, this study illuminated some unique findings of potential confidence development leading to authentic leadership.

Another participant reported that their team found them more approachable than prior to the intervention, while another reported feeling more extroverted and courageous at networking events. This openness and genuine nature could be explained through the release that the arts initiated, helping to reduce stress responses and allowing access to the part of the brain responsible for social cognition (Gupta et al., 2011). It could also be related to Fredrickson’s broaden and build theory (2001) whereby creativity and positive emotion allow for a more open and expansive demeanor. Authenticity and openness generated by the arts are important for leaders, helping teams become more innovative—a necessity for today’s ever-changing work climate (Černe et al., 2013). Through this study’s findings, there is evidence to support that engagement in the creative arts can induce positive emotions, encourage meaning, improve health, and establishing a deeper workplace connection, ultimately leading to increased productivity and accomplishment.

Limitations

One critical limitation of this study is the potential researcher bias regarding interpretations. This is due to having training and an advanced degree in art therapy; so more positive associations than neutral or negative ones could be made based on prior knowledge. A reflexive practice and a pre-acknowledged awareness of possible bias were employed to minimize this limitation.

Secondly, the validity of the data may have been affected because the convenience sample of leaders was in the immediate network; this means there was an established professional relationship with the participants prior to the study (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Therefore, some participants’ adherence to completing the intervention could be related to the researcher’s relationship. This could be seen as a compromise of the findings in that subjective sustainability and perseverance cannot be assessed. Adherence to the practice could be due to having a scheduled follow-up interview. However, this is much like a coaching relationship, whereby accountability fosters success (van Nieuwerburgh & Love, 2019). The post-intervention interview provided an incentive to complete the intervention. While the relationship with the participants could be a limitation, for this study, acquaintanceship fostered accountability to adhere and provided rich data. Henceforth, further work is needed to examine the accessibility for leaders to adhere to the 21-day program. Lastly, eleven females and two males were included in this study’s sample, which may introduce bias. To enhance generalizability and encompass a broader population, future research should strive for a balanced gender distribution.

Conclusion

This study explored the lived experiences of leaders participating in a 21-day creative arts intervention. The findings indicated a strong interconnection between the human flourishing pillars, including health, resulting in improved overall well-being. Firstly, the past exposure to and experiences with the arts set the tone for how the participants first engaged in the arts. Perceived ability did not deter participants from engaging, but it did influence modality choices. Regardless of the modality, the participants all benefitted from integrating creative arts into their daily lives. All mentioned that they would continue the practice because of the positive outcomes related to well-being. These included but were not limited to improvements in relationships and teaming in the workplace, broadening perspective, down-regulating, sleep benefits, increased stamina, and healthier lifestyle changes.

The creative practice provided positive emotions, including playfulness, joyfulness, awe, curiosity, appreciation of beauty, and a release. The consistency of daily practice allowed the participants to see those gains over the three weeks. Future studies could look at similar research measuring impacts across a larger population using a quantitative approach with a pre-PERMAH and post-PERMAH survey. The connection between health and the arts would be exciting to examine, especially concerning sleep.

Ultimately, to this researcher’s knowledge, this was the first 21-day creative arts intervention aimed at improving human flourishing among leaders. Through this intervention and valuable findings, it is plausible that optimal living can be achieved for leaders through a short daily dose of the arts.

Authors

Patricia Friberg, MSc, MPS, DProf (cand.), has a multifaceted career in positive psychology, creative arts therapy, coaching, management, and health & fitness. She hosts the podcast “Learned it from an 80s Song,” which uses music as a metaphor to inspire growth and resilience. Patricia holds postgraduate degrees in Arts Therapy and Creativity Development from Pratt Institute and MAPPCP from the University of East London. As a doctoral candidate at Middlesex University, she continues to embrace her number one VIA strength, “love of learning”.

Patricia created a mental health resilience program as part of her commitment to healthcare providers’ well-being. She collaborates with the Mental Health Initiative of Switzerland and the ICF Foundation to support Ukrainian leaders. Through her work in positive psychology, she has developed programs, including “Positive Transitions” and “Flourishing in the Workplace through the Creative Arts.” Early in her career, Patricia worked in psychiatric wards and community mental health, utilizing therapies such as DBT, mindfulness, attachment therapy, and pet therapy.

Passionate about physical well-being, Patricia contributed to the fitness industry by developing award-winning programs and DVDs that promote body positivity and reduce stress. She managed premier health clubs for a decade. Her clientele includes elite athletes, NFL and NBA players, and those recovering from injuries.

Patricia lives in Luzern, Switzerland, with her family. She immerses herself in Swiss culture and studies German. She is grateful for her feline research assistant, Hazel, who insists on proofreading every document in between naps.

Andrea Giraldez-Hayes, PhD, is a chartered psychologist, executive coaching psychologist, supervisor, psychotherapist, and consultant with a remarkable track record in academia and professional practice. With a background in education, community arts, and applied psychology, her projects have taken her worldwide, working for international organizations in the public and private sectors.

With 30 years of academic experience, Andrea was the director of the Master in Applied Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology at the University of East London between 2018 and 2023, and she is currently contributing to other academic projects. Since 2021, she has also been the chair of the Coaching Practice and Accreditations Committee at the British Psychological Society.

Andrea’s contributions to the field extend beyond her professional roles. She has authored numerous books, chapters, and articles. She is a member of the editorial boards of prestigious publications such as Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, the European Journal of Applied Positive Psychology and the International Coaching Psychology Review. Her latest edited books include Applied Positive School Psychology (2022), Arts-based Coaching: Using Creative Tools to Promote Better Self-Expression (2024) and The Routledge International Handbook of Wellbeing Arts (in press).